Kode Vicious - @kode_vicious

Kode Vicious Reloaded

A koder with attitude, KV answers your questions. Miss Manners he ain’t.

Although he is loath to admit it, Kode Vicious thrives on dispensing free advice to koders in need. But without your continuous stream of queries, he begins to wither or, worse, behave in a reckless and dangerous manner that, quite frankly, scares the heck out of us. And so, we beseech you, help us keep him at bay by sending your koding questions to [email protected]. His wisdom (and acerbic wit) awaits...

Dear KV,

I’ve been working on a program in C++ to handle some simple data analysis at my company. The program should be a small project, but every time I start specifying the objects and methods it seems to grow to a huge size, both in the number of lines and the size of the final program. I think the problem is that there are just too many things in the system to analyze and each one needs a special case, which requires just a bit more code, or another subclass to be created. Help!

Driven to Abstraction

Dear DA,

One of the biggest problems when people use an object-oriented language is that when they realize how easy it is to create yet another class, they do. Instead of figuring out where the rubber meets the road, they instead find where the rubber meets the sky.

Of course without looking at your code—and given your description I really don’t want to look at your code—I can’t give you a pat answer. I also charge heavily for pat answers.

When I find someone I work with spending days specifying class after class without writing any implementation code, I first take a long walk around the building. My therapist says that screaming at people helps no one. I don’t agree with him, but for now, I am playing along.

I have a few pieces of advice when you find that something you think should be simple starts to take up a huge amount of time and space. The first suggestion is to switch from a compiled language, such as C++, to something interpreted, such as BASIC. Oh, wait, sorry, not BASIC. I meant Python, my current scripting language of choice. The reason I suggest Python is because it, too, is object-oriented, and it’s easier to move an idea built in one OO language to another. You may even find that Python suits your needs perfectly and you won’t have to move to a compiled language, but that decision is further off.

I suggest a scripted language because of my second piece of advice. Try to solve a smaller part of the problem. Programmers and engineers often try to bite off more than they can chew. We’re a strangely optimistic lot, unless we’re talking to a marketing person. In that case solving an equation such as 2 + 2 seems to require millions of dollars in investment, a colo full of machines, high-speed network links to everyone’s house, and six weeks of paid vacation in Barcelona if you come up with a correct result. Maybe you don’t handle your marketing people that way, but I can’t suggest it strongly enough.

With a scripting language you can take smaller bites of the problem and play with them. If you can solve a part of the problem and get some output to work with, you can then probably figure out the next five or six things to do and do them and so on. The nice thing about working in smaller chunks is that you wind up with a result a lot sooner, and that’s a lot more satisfying than having reams of UML diagrams and hand waving and a promise of a brave new world when you’re done, which, at the rate you’re going, you probably never will be.

So, get your tires out of the clouds, put them on the road, and implement a few things, instead of trying to solve everything at once.

KV

*

Dear KV,

I work for a company that builds all kinds of different Web applications. We do everything from blogs and news sites to mail and financial systems. It depends on what the customer wants.

Right now our biggest problem at work is the number of bugs we have that relate to input validation. These bugs are totally maddening because each time one of them is fixed, some other problem pops up in the same code, and the checking code is getting very close to spaghetti. Is there any way out of this tangle without some mythical technology, such as natural language understanding?

Input Invalid

Dear II,

You’ve come across one of the biggest programming problems since the day we stupidly let non-engineers (i.e., users) touch our nice toys. Of course, computers aren’t really very useful if they don’t do something for actual people, but it is a pain. Systems would be so much cleaner without people. Alas, user input is a fact of life, and one that we all have to work with every day. User input is also one of the biggest sources of security holes in software, as any reader of the BugTraq mailing list can tell you.

The first rule of handling user input is, “TRUST NO ONE!”, in particular your users. Although I’m sure 90 percent of them are perfectly nice people who go to their religious shrine of choice at the appointed time every week, or whatever it is perfectly nice people do (I don’t actually know any perfectly nice people, but I have heard about them), there are the usual minority of thieves, jerks, and just plain idiots who will look at your nice Web form as a place to steal money, play tricks, and generally cause havoc. The rest of the people, the perfectly nice ones whom I’ve never met, won’t actually attack your system; they’ll just use it in a way they think is logical, and if their logic and your logic do not match, kaboom! Kode Vicious hates kabooms. They mean late nights, and complaints from my doctor about alcohol and caffeine intake. I can’t help it if he’s stingy with the prescription meds, but let’s not get into that now.

The second rule is, “DON’T TRUST YOURSELF!” This is another way of saying that you should check your results to make sure you’re not missing anything. Just because you sent something to the users does not mean that they didn’t do something a bit odd to it before it came back to you. A quick example is a Web form: if you depend on the data you sent in a Web form to users, you had better check the whole form, and not just the parts you expected the users to change with their browsers. It’s a simple trick to exploit an error in form submission code by sending a slightly changed form with proper user input.

It sounds, from your description, as if the system you’re using was written using what is called a blacklist. This is a set of rules that says which things are bad. During the Cold War the United States maintained blacklists to prevent people it didn’t like from getting jobs. Your name is on the list, sorry, no job. In the same way, software uses blacklists to say which types of operations, in this case user input, are bad. The problem with blacklists is that they are hard to maintain. They start off simple enough, saying things like, “Do not accept input with URLs in them,” but quickly get out of hand, with lists of the names for JavaScript, of which there are many, and different types of tags to check for, and, and, and... I hope you get the idea. It is better to use whitelists where this is possible.

A whitelist, unsurprisingly, is the opposite of a blacklist. Whitelists contain only the things that are allowed, and are often very short. An example is, “Accept only ASCII alphabetic characters.” Whitelists can be very restrictive but they have a distinct advantage over blacklists in that the only time you have to change a whitelist it to make it more permissive. A blacklist is, by default, mostly permissive, with the few exceptions that are the entries in the list.

My recommendation is to switch to using whitelists and to be very restrictive in what the user can give to you. Initially this seems a bit draconian, but it’s probably the best way to protect your code, both from users and from turning into spaghetti.

KV

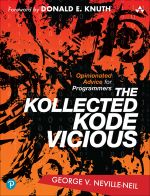

KODE VICIOUS, known to mere mortals as George V. Neville-Neil, works on networking and operating system code for fun and profit. He also teaches courses on various subjects related to programming. His areas of interest are code spelunking, operating systems, and rewriting your bad code (OK, maybe not that last one). He earned his bachelor’s degree in computer science at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts, and is a member of ACM, the Usenix Association, and IEEE. He is an avid bicyclist and traveler who has made San Francisco his home since 1990.

© 2005 ACM 1542-7730/05/0300 $5.00

Got a question for Kode Vicious? E-mail him at [email protected]—if you dare! And if your letter appears in print, he may even send you a Queue coffee mug, if he’s in the mood. And oh yeah, we edit letters for content, style, and for your own good!

![]()

Originally published in Queue vol. 3, no. 2—

Comment on this article in the ACM Digital Library

More related articles:

Dennis Roellke - String Matching at Scale

String matching can't be that difficult. But what are we matching on? What is the intrinsic identity of a software component? Does it change when developers copy and paste the source code instead of fetching it from a package manager? Is every package-manager request fetching the same artifact from the same upstream repository mirror? Can we trust that the source code published along with the artifact is indeed what's built into the release executable? Is the tool chain kosher?

Catherine Hayes, David Malone - Questioning the Criteria for Evaluating Non-cryptographic Hash Functions

Although cryptographic and non-cryptographic hash functions are everywhere, there seems to be a gap in how they are designed. Lots of criteria exist for cryptographic hashes motivated by various security requirements, but on the non-cryptographic side there is a certain amount of folklore that, despite the long history of hash functions, has not been fully explored. While targeting a uniform distribution makes a lot of sense for real-world datasets, it can be a challenge when confronted by a dataset with particular patterns.

Nicole Forsgren, Eirini Kalliamvakou, Abi Noda, Michaela Greiler, Brian Houck, Margaret-Anne Storey - DevEx in Action

DevEx (developer experience) is garnering increased attention at many software organizations as leaders seek to optimize software delivery amid the backdrop of fiscal tightening and transformational technologies such as AI. Intuitively, there is acceptance among technical leaders that good developer experience enables more effective software delivery and developer happiness. Yet, at many organizations, proposed initiatives and investments to improve DevEx struggle to get buy-in as business stakeholders question the value proposition of improvements.

João Varajão, António Trigo, Miguel Almeida - Low-code Development Productivity

This article aims to provide new insights on the subject by presenting the results of laboratory experiments carried out with code-based, low-code, and extreme low-code technologies to study differences in productivity. Low-code technologies have clearly shown higher levels of productivity, providing strong arguments for low-code to dominate the software development mainstream in the short/medium term. The article reports the procedure and protocols, results, limitations, and opportunities for future research.