Kode Vicious - @kode_vicious

Halfway Around the World

Learn the language, meet the people, eat the food

Dear KV,

My company has asked me to spend six months helping to start a software development group in a place halfway around the world from where we are based now. I did not get this assignment because I have seniority with the company; quite the opposite—they seem to be sending me because I am one of the youngest people and one of the few developers without a partner or children.

I'm told the developers I'll be working with are fluent in English, which I would expect in technology, but outside of work, I'll need either an interpreter or lessons to learn the local language. I was never good at languages in school, except for the ones I programmed in, and I worry I have no ear for them. I figure since it's a relatively short period of time, I can just work a lot, talk to friends at home over the Internet, avoid the whole language-learning problem, and then return home at the end of six months (with a promotion and better pay).

Have you ever had to manage a group where the developers spoke another language, or, perhaps, done a stint outside the U.S.?

Mono Lingual

Dear Mono,

No one in their right mind, not even the dumbest executive, would ask KV to manage a group of people, whether that group spoke English, Spanish, Mandarin, or Klingonese, but I have been lucky enough to work in several places outside my home country, and each time I have found it to be at equal turns challenging, frustrating, and rewarding.

Let me first disabuse you of the idea that the language classes you took in middle or high school had anything to do with language learning. The teaching of human languages in schools in the U.S. and in many other countries, is, well... I can't say it's a joke, because jokes are funny, and your typical French, German, or Spanish classes, which were the options when KV was in school, were uniformly awful. Human beings do not learn languages by studying a grammar book or reciting the conjugations of verbs; they learn languages by listening and speaking. Have you ever seen a two-year-old with a grammar book? I didn't think so. Forget everything you thought you learned about whatever language you took in school and start fresh when you get to your assignment.

Human languages also have a built-in reward system: Say the right thing and you get breakfast; say it incorrectly, and you may be eating a dog's breakfast. Yes, you should learn the language of the locale you are planning to live in, and here are a few good reasons why. The first is that you will not always be at work; something might happen—a car might break down, or the metro; or there could be a fire in your apartment building—there are always going to be situations where handling the local language is important. Emergencies aside, you will have a much more interesting experience if you can at least get by in a language, rather than constantly pointing at picture menus. Finally, it has been shown that learning languages increases brain function, which, as scientists and engineers, must surely be something we all want.

Apart from the differences in language, every place—not just different countries, but also cities, provinces, and all the other possible delineations on this planet—has a different culture, both at and outside of work. You cannot insulate yourself from the culture by becoming a robot who only goes from home to work and then back. Even if you hid in your house, eating expensive imported food and consuming entertainment from home over the 'net, you would still have to go out and work with this group that you're supposed to be managing. How can you hope to manage people whose lives and motivations you have made no effort to understand? Don't answer, because the answer is easy: You can't.

If you think you find different ways of working when you switch companies, that's nothing compared with the differences you'll find every day when you arrive at the office in a different country. What time do people arrive? Do they stay late? How late is late? How do they see their work? How do they solve problems? In software and computer science, we like to think that our common language is that of algorithms and math, and while that is, in part, true, it is nowhere near the totality of what it means to be working together.

KV has always made the point that software is a collaborative, human endeavor, and that the things we do to make computers (mostly) do what we say are actually only a small part of our work. Most of the work of software is building systems that we can explain to each other, and even if everyone on the team, or in the room, or whatever, is speaking the same mathematical and even human language, the culture of the people involved comes into play time and again.

A simple case in point. There are places where certain features can or cannot be built into software, not only due to varying forms of regulation, but also because of cultural expectations about what is and what is not acceptable practice. These vary from company to company, as I pointed out, but they vary far more widely among cultures. A French developer, a Chinese developer, and an American developer all walk into a bar... Wait, no, they all think differently about features they are asked to deliver, and knowing what to expect from whichever one you happen to be working with is going to be a part of succeeding in your six-month assignment.

Not only do different cultures treat different features differently, but they also treat each other differently. How people act with respect to each other is a topic that can, and does, fill volumes of books that, as nerds, we probably have never read, but finding out a bit about where you're heading is a good idea. You can try to ask the locals, although people generally are so enmeshed in their own cultures that they have a hard time explaining them to others. It's best to observe with an open mind, watch how your new team reacts to each other and to you, and then ask simple questions when you see something you don't understand.

KV's advice—whenever asked about a gig in a different country—is always the same: Learn the language, meet the people, eat the food, and only be rude on purpose; never give offense by mistake, which is why you need to learn at least a bit of the local language. People don't speak Java, for which we should all be eternally thankful.

Kode Vicious

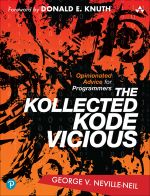

George V. Neville-Neil works on networking and operating-system code for fun and profit. He also teaches courses on various subjects related to programming. His areas of interest are computer security, operating systems, networking, time protocols, and the care and feeding of large code bases. He is the author of The Kollected Kode Vicious and co-author with Marshall Kirk McKusick and Robert N. M. Watson of The Design and Implementation of the FreeBSD Operating System. For nearly 20 years, he has been the columnist better known as Kode Vicious. Since 2014, he has been an industrial visitor at the University of Cambridge, where he is involved in several projects relating to computer security. He earned his bachelor's degree in computer science at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts, and is a member of ACM, the Usenix Association, and IEEE. His software not only runs on Earth, but also has been deployed as part of VxWorks in NASA's missions to Mars. He is an avid bicyclist and traveler who currently lives in New York City.

Copyright © 2023 held by owner/author. Publication rights licensed to ACM.

![]()

Originally published in Queue vol. 21, no. 4—

Comment on this article in the ACM Digital Library

More related articles:

João Varajão, António Trigo - Assessing IT Project Success: Perception vs. Reality

This study has significant implications for practice, research, and education by providing new insights into IT project success. It expands the body of knowledge on project management by reporting project success (and not exclusively project management success), grounded in several objective criteria such as deliverables usage by the client in the post-project stage, hiring of project-related support/maintenance services by the client, contracting of new projects by the client, and vendor recommendation by the client to potential clients. Researchers can find a set of criteria they can use when studying and reporting the success of IT projects, thus expanding the current perspective on evaluation and contributing to more accurate conclusions.

Abi Noda, Margaret-Anne Storey, Nicole Forsgren, Michaela Greiler - DevEx: What Actually Drives Productivity

Developer experience focuses on the lived experience of developers and the points of friction they encounter in their everyday work. In addition to improving productivity, DevEx drives business performance through increased efficiency, product quality, and employee retention. This paper provides a practical framework for understanding DevEx, and presents a measurement framework that combines feedback from developers with data about the engineering systems they interact with. These two frameworks provide leaders with clear, actionable insights into what to measure and where to focus in order to improve developer productivity.

Jenna Butler, Catherine Yeh - Walk a Mile in Their Shoes

Covid has changed how people work in many ways, but many of the outcomes have been paradoxical in nature. What works for one person may not work for the next (or even the same person the next day), and we have yet to figure out how to predict exactly what will work for everyone. As you saw in the composite personas described here, some people struggle with isolation and loneliness, have a hard time connecting socially with their teams, or find the time pressures of hybrid work with remote teams to be overwhelming. Others relish this newfound way of working, enjoying more time with family, greater flexibility to exercise during the day, a better work/life balance, and a stronger desire to contribute to the world.

Bridget Kromhout - Containers Will Not Fix Your Broken Culture (and Other Hard Truths)

We focus so often on technical anti-patterns, neglecting similar problems inside our social structures. Spoiler alert: the solutions to many difficulties that seem technical can be found by examining our interactions with others. Let’s talk about five things you’ll want to know when working with those pesky creatures known as humans.